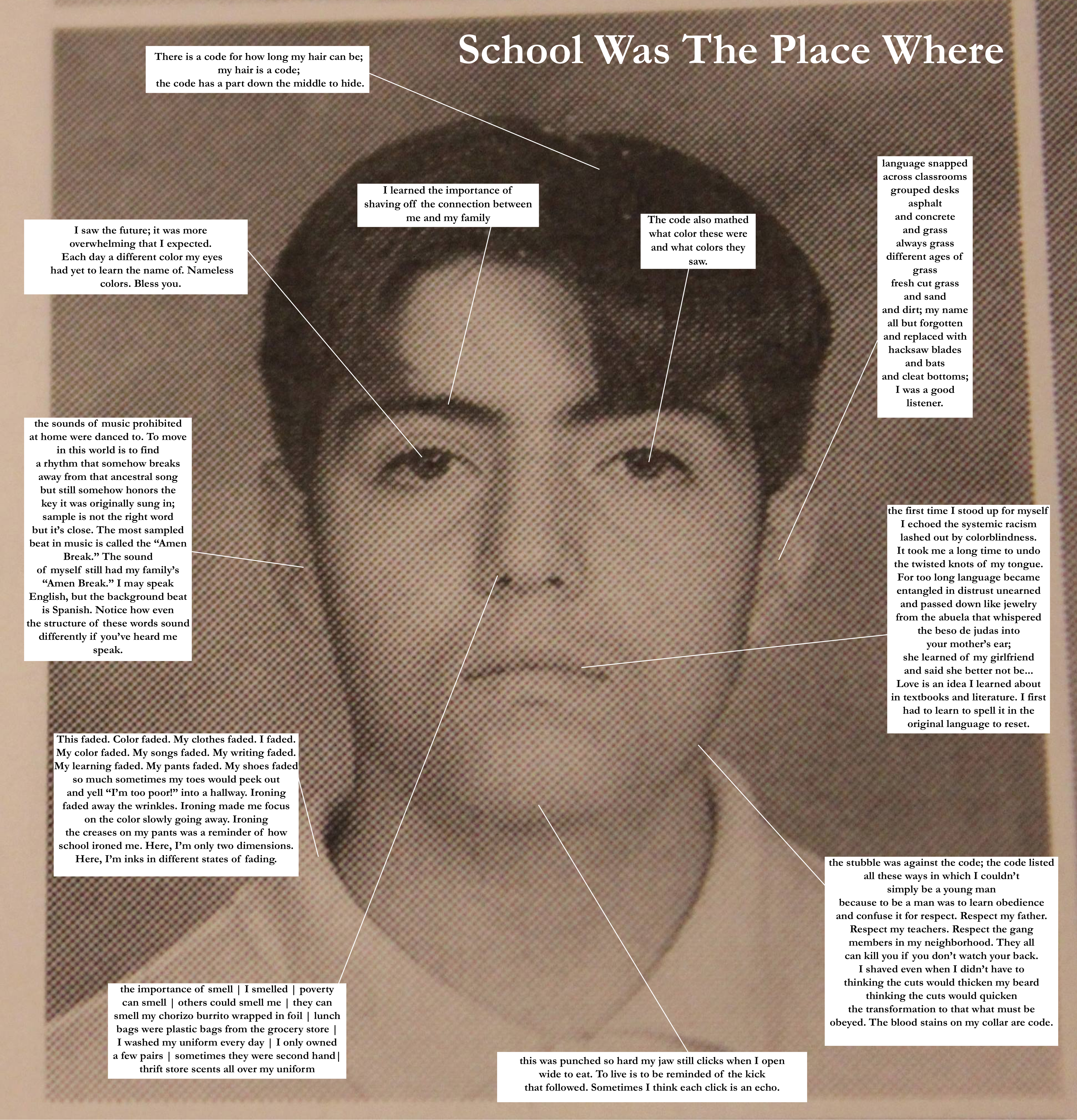

read image description (alt text)

Artist’s Statement: In the article “The Resegregation of Jefferson County,” Nikole Hannah-Jones writes that “since 2000, at least 71 communities across the country, most of them white and wealthy, have sought to break away from their public-school districts to form smaller, more exclusive ones.” This led to research into my state’s segregation and integration efforts. The rhetoric, the maps, and the data were all there—coded language, school boundaries, and even diversity statements covered the stagnant “struggle” toward integration. As an educator, this project provided context for my experience and those of the students in the classroom. Notes and citations will appear at the end of the project.