Brian Turner

Today’s poem (“Clutch”) is the only one that’s out of order (and not written ‘today’). I hope you don’t feel cheated! I’m still in the marathon, only I knew in advance that I needed to interview memoirist Jerad Alexander for the Miami Book Fair (with a conversation about his wonderful new book, Volunteers, due out November 9th). In anticipation of that, I wrote “Clutch” the same day I wrote “Lena Blackburne Baseball Rubbing Mud.” In fact, in this video one can see that the baseball rubbing mud shows up here, but then I took it out. I realized it was weighing the meditation down and that there were two poems vying for space within one poem—so I pulled those lines out and tried to remain focused on what was happening inside the landscape you’ll see in the poem below.

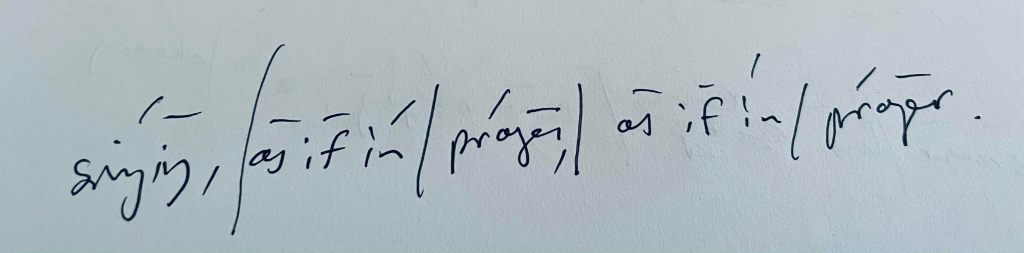

One quick note on the photograph. I know that I’ve marked anapests where there are no anapests—but that’s how I think of it in reading it, those ‘ins’ almost italicized, given stress, leaning into the idea of inside/within, within prayer, inside of it, as if in prayer…

Clutch

The splitter is part of the fastball genre—David Cone

Baseball has a way of illuminating us.

The nine-hole hitter steps up to the plate, the game

in the balance, tied at two apiece, something

special about to happen. Everything

hushed around this moment. He has struck out

all night, and maybe most of his life, but tonight,

on this one pitch, a splitter choked-up deep

in the webbing between the index and middle

fingers of the pitcher’s dominant hand,

the thumb anchored below, that cowhide stretched

and tanned with aluminum salts, the ball,

yes, it’s true, stitched by hand at a Rawlings plant

in Turrialba, Costa Rica, where

190 workers lost their jobs

last year, though the plant remains open, that ball

spins midair on its way toward home, the seams

barely moving as the ball appears to float—

as if in slow motion, as if pausing

to appreciate the sublime when it appears.

If we could pause a moment to ask him—why

this game designed to induce failure, why play

a sport that humbles us with each at bat?

And, of course, the answer is here, in this moment,

the count one ball, two strikes, the bat tracing

an invisible arc on a geometric plane

which this ball has traveled so very far to meet.

And when it launches into the night sky, deep

and sweet and blue-black and god-damn beautiful,

the crowd becomes a sound that’s all but gone,

because his body thrums with voices that sing

from a country across the water, green mountains

away, voices in his mother tongue, loved ones

he hears as he rounds the diamond, those voices

singing, a kind of prayer, a kind of prayer.